Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Researchers at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) are developing a sensor the size of a Band-Aid that will measure a baby's blood oxygen levels, a vital indication of the lungs' effectiveness and whether the baby's tissue is receiving adequate oxygen supply. Unlike current systems, this miniaturized wearable device will be flexible and stretchable, wireless, inexpensive, and mobile – possibly allowing for remote monitoring from home.

Ulkuhan Guler, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering and director of WPI's Integrated Circuits and Systems Lab, is leading the project focused on enabling sick, hospitalized babies to be untethered from wired sensors, so they can more easily and frequently be examined, held, and even allowed to go home. Guler and her team have developed a miniature oxygen monitor for babies, which measures blood gases diffusing through the skin and reports the data wirelessly.

Typically, measuring oxygen molecule levels transcutaneously involves using a system with an approximately 5-pound monitor plugged into an electrical outlet, and sensors that generally are wired to the monitor. Guler's healthcare device will use wireless power transfer. It also will be connected to the Internet wirelessly so an alarm on a monitor in a doctor's office or smartphone app would notify medical personnel and family members if the baby's oxygen level begins to drop.

The device is designed to measure PO2, or the partial pressure of oxygen, which indicates the amount of oxygen dissolved in the blood – a more accurate indicator of respiratory health than a simple oxygen saturation measurement, which can be easily taken with a pulse oximetry device gently clamped on a finger. And measuring the PO2 level via a noninvasive device attached on the skin is as accurate as a blood test.

The wearable baby oxygen monitor also would be useful for adults, especially people with severe asthma and seniors with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, which is an incurable, progressive lung disease and the third leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guler will modify the wearable for adults, and create a related smartphone app, in another phase of her research.

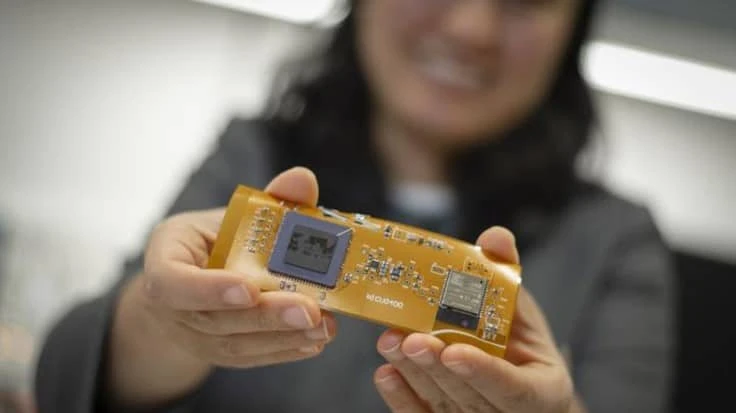

Guler is collaborating with Pratap Rao, associate professor of mechanical engineering at WPI, and Lawrence Rhein, MD, chair of the department of pediatrics and an associate professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Ian Costanzo and Devdip Sen, both graduate students in electrical and computer engineering at WPI, also are working with Guler to create a chip that will eventually act as the heart for the wearable device.

The chip, designed to work inside the wearable oxygen monitor, activates the optical sensors, captures analogue signals from the sensor, handles power management, and contains required circuitry. Guler and the team have custom designed the individual circuits, such as signal capturing circuits and driver circuits for optical based read-out circuits. In the next phase of the research project, they plan to equip the chip with more circuitries to digitize the analogue signals, transmit the captured and digitized data, and create power from a wireless link. At that point, it will be a complete system on the chip.

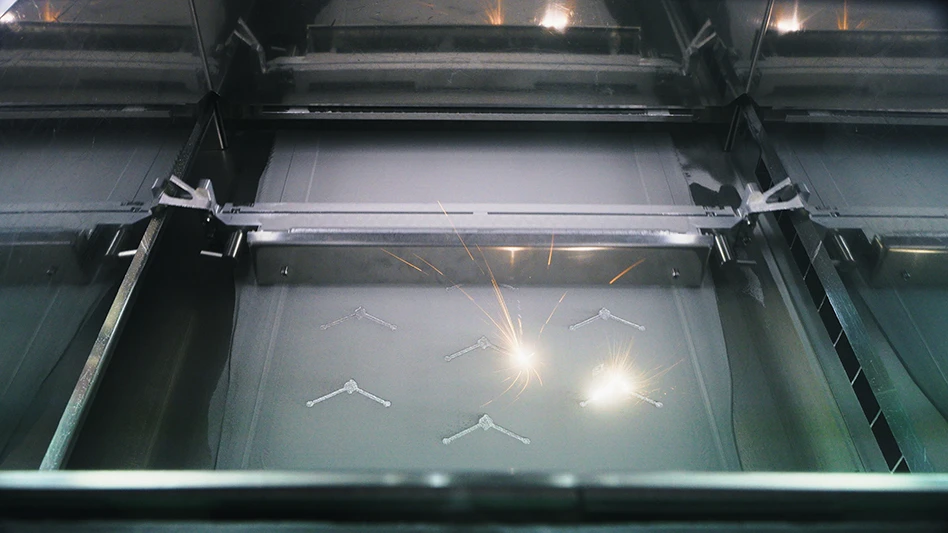

In an interdepartmental collaboration, Guler and Rao are creating miniaturized thin and flexible sensors for the wearable healthcare devices so they will be comfortable and secure on the babies while they're moving.

"The concept of the technology is that if we have more accessible data for a person of any age, we'll be able to better take care of these patients," says Rhein, who has been advising Guler on what's needed in a hospital and home setting. "The idea of noninvasive, untethered, accessible data collection opens up a whole new world of care."

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- HERMES AWARD 2025 – Jury nominates three tech innovations

- Vision Engineering’s EVO Cam HALO

- How to Reduce First Article Inspection Creation Time by 70% to 90% with DISCUS Software

- FANUC America launches new robot tutorial website for all

- Murata Machinery USA’s MT1065EX twin-spindle, CNC turning center

- #40 - Lunch & Learn with Fagor Automation

- Kistler offers service for piezoelectric force sensors and measuring chains

- Creaform’s Pro version of Scan-to-CAD Application Module