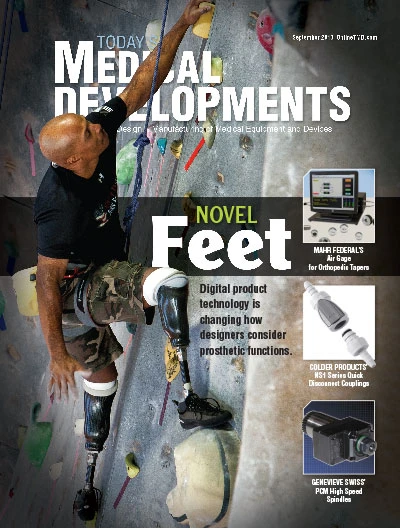

Christian Redd, a University of Washington doctoral student in bioengineering, measures and marks where the electrodes will be placed on Ron Bailey’s leg. The electrodes connect to a portable device that tracks the swelling and shrinking of his limb. Christian Redd, a University of Washington doctoral student in bioengineering, measures and marks where the electrodes will be placed on Ron Bailey’s leg. The electrodes connect to a portable device that tracks the swelling and shrinking of his limb. |

When Ron Bailey lost his right leg below the knee 10 years ago after a head-on collision, he was fitted with a prosthetic leg and began learning to use it in his daily life as a real estate agent in Federal Way, Wash.

For a couple of years after the amputation, Bailey, 66, says the remaining part of his leg shrank, which is common after the surgery. This caused him discomfort in the socket, the connection point of his limb to the prosthesis. To make it comfortable enough to wear, Bailey swapped out sockets of different sizes and used fabric pieces called socks to cushion the impact and adjust the fit.

“In the end, the socket is the most important part,” Bailey says. “You can have a great prosthetic foot, but if the socket isn’t comfortable, you’re not going to wear it.”

Many people who use prostheses experience pain on a daily basis where their skin meets the socket, particularly those who have diabetes or other diseases that affect their physiology.

University of Washington engineers aim to ease this discomfort with research that could help build better sockets. They have developed a device that tracks how much a person’s limb swells and shrinks when it’s inside a prosthetic socket. The data could help doctors and patients predict how and when their limbs will swell, which could be used to build smarter sockets.

The device fits in a fanny pack and thin wires feed data from electrodes into the device. The device fits in a fanny pack and thin wires feed data from electrodes into the device. |

“This provides us a window into what’s happening,” states principal investigator Joan Sanders, a UW professor of bioengineering. “I’m really encouraged by what we have so far.”

Soft tissues in a prosthesis socket swell and shrink often during the day, a natural fluctuation that happens when we increase physical activity, sit or stand, and even eat salty foods. However, in a fixed socket, these fluid volume changes can be particularly painful, forcing people to seek relief by removing their artificial limb or adjusting the snugness of the fit by adding or removing fabric socks.

If physicians can track when an individual typically experiences volume changes in his or her prosthesis socket, they can better fit patients with artificial limbs and reduce the amount of pain, states Kate Allyn, the team’s lead research prosthetist who has worked for years making and fitting artificial limbs to patients.

The device measures the percent increase or decrease of fluid volume in a patient’s limb by receiving data from small electrodes placed in different spots on the leg. Instrument electronics can be worn in a fanny pack and include a circuit board that calculates the fluid volume change in the leg tissues, transmitting the data wirelessly to a computer or storing it on the device. During the past two years, engineers tested a larger prototype on about 60 patients in their Seattle, Wash., lab. Now they have a checkbook-sized portable version that they have brought to clinics in Seattle and San Francisco, Calif.

Researchers are testing the device by asking patients to go through a routine that includes sitting, standing, and walking as the device records fluid changes. In the UW lab, Bailey does a series of 90-second exercises while wearing the portable device. Data is transmitted wirelessly to a tablet that displays the changes in his limb size about 15 times a second. Ten years after his accident, Bailey can do nearly everything he enjoyed before – pain free. Nevertheless, he still experiences shrinkage in his residual limb, and for the past eight years he has helped the UW team test various prototype devices and instruments.

Top: University of Washington research scientist Dave Gardner places electrodes on Ron Bailey’s residual limb. Middle: Electrodes with a sticky backing are placed at various points on the leg. They track the fluid volume changes within the leg. Bottom: The portable device that tracks fluid volume changes. The electrodes fasten to a patient’s leg in order to transmit data to the device. Top: University of Washington research scientist Dave Gardner places electrodes on Ron Bailey’s residual limb. Middle: Electrodes with a sticky backing are placed at various points on the leg. They track the fluid volume changes within the leg. Bottom: The portable device that tracks fluid volume changes. The electrodes fasten to a patient’s leg in order to transmit data to the device. |

In the near term, researchers hope clinics could go through a similar routine to help track an individual’s swelling and shrinking patterns.

“Each person has his or her own characteristics and qualities that affect how limb volume changes,” Sanders says. “You really have to look at each person on a case-by-case basis.”

Longer term, researchers want to build a smaller device that patients could wear for a couple of weeks or longer to monitor changes in their limb size as they go about their daily routines.

The hope is that prosthetic limb sockets will become more robust and flexible, accommodating natural changes in swelling without causing discomfort or inconvenience. The UW device is promising for understanding how to design these smart prostheses, Allyn says.

This summer, the team worked with patients across the U.S. and Canada who use vacuum-suction technology to help keep their residual limbs snug in the sockets and adjust the fit when tissues swell and shrink. Patients say this vacuum can help improve socket comfort and reduce pain, but the technology requires careful maintenance, and it can be disruptive when the noisy vacuum turns on.

The research team is working with Seattle-based companies Spencer Technologies on building the hardware and D.E. Hokanson Inc. on the design.

The research is funded by a four-year, $2.6 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense.

The original article is from the University of Washington and was authored by Michelle Ma; mcma@uw.edu; www.washington.edu.

Explore the September 2013 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- UCIMU: fourth quarter 2024 machine tool orders on the rise

- Thomson Industries’ enhanced configuration capabilities

- Frequently Asked Questions about AM Post Processing

- How new executive orders may affect US FDA medical device operations

- Midwest DISCOVER MORE WITH MAZAK

- Reshoring survey to provide insight for US industrial policy

- NB Corporation of America's ball splines

- AdvaMed seeks medical technology exemption from all tariffs