Photo: Jospeh Ciolino MD with contact lens. Credit: John Earle Photography

Boston, Massachusetts – A medical device in the form of a contact lens is designed to deliver medication gradually to the eye could improve outcomes for patients with conditions requiring treatment with eye drops, which are often imprecise and difficult to self-administer. In a study published online in Ophthalmology, a team of researchers have shown that a novel contact lens-based system, which uses a strategically placed drug polymer film to deliver medication gradually to the eye, is at least as effective, and possibly more so, as daily latanoprost eye drops in a pre-clinical model for glaucoma.

“We found that a lower-dose contact lens delivered the same amount of pressure reduction as the latanoprost drops, and a higher-dose lens, interestingly enough, had better pressure reduction than the drops in our small study,” said first author Joseph B. Ciolino, M.D., an ophthalmologist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and an Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School. “Based on our preliminary data, the lenses have not only the potential to improve compliance for patients, but also the potential of providing better pressure reduction than the drops.”

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in the world. While there is no cure for glaucoma, ocular medications aim to lower pressure in the eye with the goal of preventing vision loss. Currently, the medications are delivered as eye drops, which sometimes cause stinging and burning, can be difficult to self-administer and are subsequently associated with poor patient compliance, with some studies suggesting that compliance is as low as 50 percent.

“This promising delivery system removes the burden of administration from the patient and ensures consistent delivery of medication to the eye, eliminating the ongoing concern of patient compliance with dosing,” said Janet B. Serle, M.D., a glaucoma specialist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Contact lenses have been studied as a means of ocular drug delivery for nearly 50 years, yet many such lenses are ineffective because they dispense the drug too quickly. The authors of the Ophthalmology study designed the contact lens to allow for a more controlled drug release. The researchers had previously shown in a 2014 study that the lens is capable of delivering medication continuously for one month.

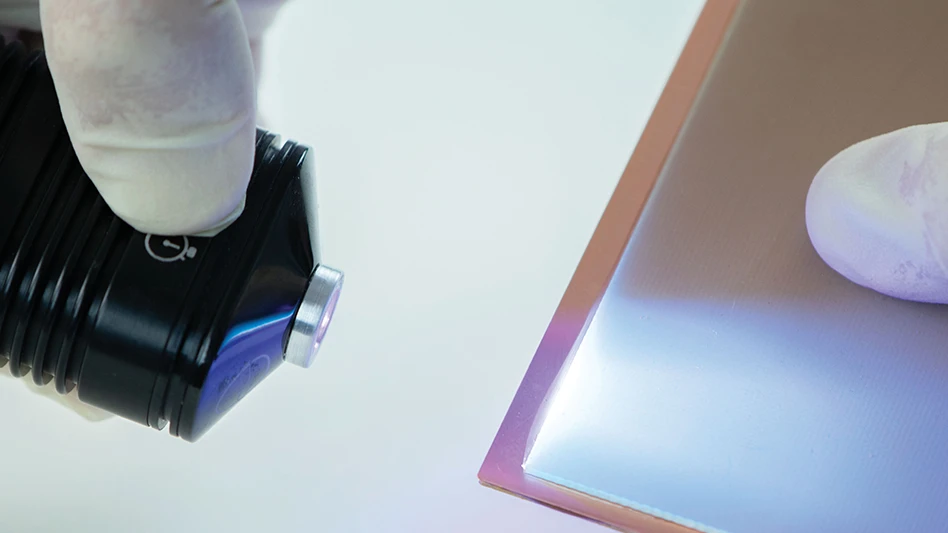

The researchers designed a novel contact lens that contains a thin film of drug-encapsulated polymers in the periphery. The drug-polymer film slows the drug coming out of the lens. Because the drug film is on the periphery, the center of the lens is clear, allowing for normal visual acuity, breathability and hydration. The lenses can be made with no refractive power or with the ability to correct the refractive error in nearsighted or farsighted eyes.

“Instead of taking a contact lens and allowing it to absorb a drug and release it quickly, our lens uses a polymer film to house the drug, and the film has a large ratio of surface area to volume, allowing the drug to release more slowly,” said senior author Daniel S. Kohane, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery at Boston Children’s Hospital.

In a study supported by a grant from the Boston Children’s Hospital Technology and Innovation Development Office, the effect of this drug eluting contact lens was assessed in four glaucomatous monkeys. The researchers showed that the contact lens with lower doses of latanoprost delivers the same amount of eye pressure reduction as the eye drop version of the medication. The lenses delivering higher doses of latanoprost had better pressure reduction than the drops. Further study is needed to confirm the finding in the higher-dose lenses.

The researchers are currently designing clinical trials to determine safety and efficacy of the lenses in humans.

“If we can address the problem of compliance, we may help patients adhere to the therapy necessary to maintain vision in diseases like glaucoma, saving millions from preventable blindness,” said Dr. Ciolino. “This study also raises the possibility that we may have an option for glaucoma that’s more effective than what we have today.”

In addition to Drs. Ciolino, Kohane and Serle, co-authors of the Ophthalmology report include Amy E. Ross, M.Sc., Rehka Tulsan, M.Sc., and Amy C. Watts, O.D., of Massachusetts Eye and Ear, David Zurakowski, Ph.D. of Boston Children’s Hospital and Rong-Fang Wang, M.D., of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The research was supported by a grant from the Technology and Innovation Development Office of Boston Children’s Hospital, the National Eye Institute 1K08EY019686-01, the Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund, the New England Cornea Transplant Fund, the Eleanor and Miles Shore Foundation and Research to Prevent Blindness.

About Massachusetts Eye and Ear

Mass. Eye and Ear clinicians and scientists are driven by a mission to find cures for blindness, deafness and diseases of the head and neck. Now united with Schepens Eye Research Institute, Mass. Eye and Ear is the world's largest vision and hearing research center, developing new treatments and cures through discovery and innovation. Mass. Eye and Ear is a Harvard Medical School teaching hospital and trains future medical leaders in ophthalmology and otolaryngology, through residency as well as clinical and research fellowships. Internationally acclaimed since its founding in 1824, Mass. Eye and Ear employs full-time, board-certified physicians who offer high-quality and affordable specialty care that ranges from the routine to the very complex. In the 2016–2017 “Best Hospitals Survey,” U.S. News & World Report ranked Mass. Eye and Ear #1 in the nation for ear, nose and throat care and #1 in New England for eye care.

About Boston Children’s Hospital

Boston Children’s Hospital is home to the world’s largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center, where its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. More than 1,100 scientists, including seven members of the National Academy of Sciences, 14 members of the Institute of Medicine and 14 members of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute comprise Boston Children’s research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children’s today is a 395-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. Boston Children’s is also the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School.

About Harvard Medical School Department of Ophthalmology

The Harvard Medical School (HMS) Department of Ophthalmology (eye.hms.harvard.edu) is one of the leading and largest academic departments of ophthalmology in the nation. More than 350 full-time faculty and trainees work at nine HMS affiliate institutions, including Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Joslin Diabetes Center/Beetham Eye Institute, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, VA Maine Healthcare System, and Cambridge Health Alliance. Formally established in 1871, the department has been built upon a strong and rich foundation in medical education, research, and clinical care. Through the years, faculty and alumni have profoundly influenced ophthalmic science, medicine, and literature – helping to transform the field of ophthalmology from a branch of surgery into an independent medical specialty at the forefront of science.

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- Copper nanoparticles could reduce infection risk of implanted medical device

- Renishaw's TEMPUS technology, RenAM 500 metal AM system

- #52 - Manufacturing Matters - Fall 2024 Aerospace Industry Outlook with Richard Aboulafia

- Tariffs threaten small business growth, increase costs across industries

- Feed your brain on your lunch break at our upcoming Lunch + Learn!

- Robotics action plan for Europe

- Maximize your First Article Inspection efficiency and accuracy

- UPM Additive rebrands to UPM Advanced